When caring for a parent with dementia at home, a family caregiver’s decisions suddenly feel more complex. Even for the most prepared family members, the weight of the new diagnosis can seem overwhelming.

Having an understanding of what dementia looks like helps to make caring for the senior easier. Arm yourself with information about how the disease progresses. Explore tips for supporting your parent with dementia and find support groups to minimize anxiety and uncertainty. Combined, this knowledge increases opportunities for a higher quality of life.

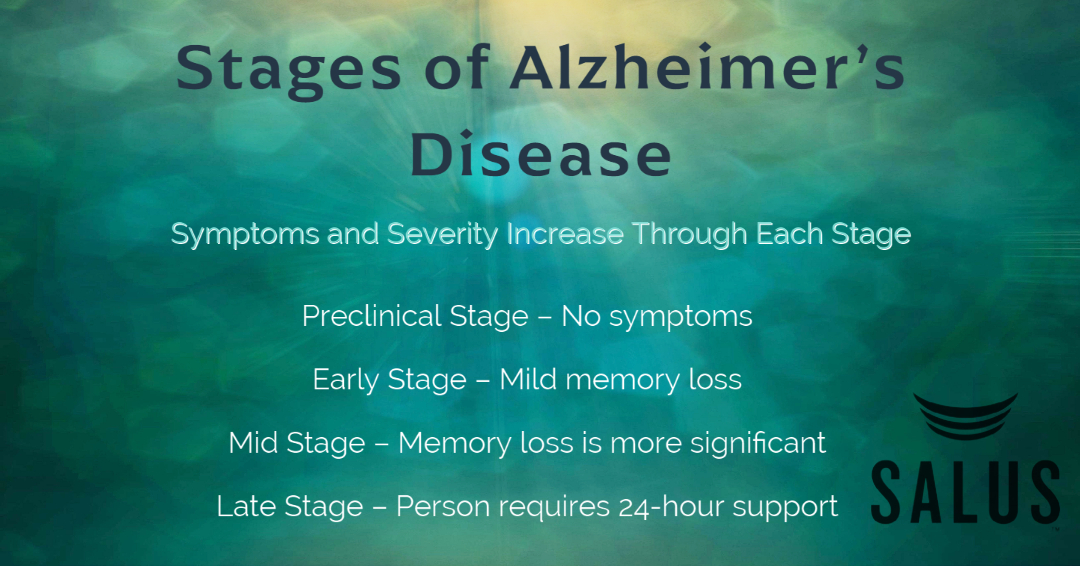

Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, Alzheimer’s accounts for sixty to eighty percent of dementia cases. Every person with Alzheimer’s disease experiences it in a unique way. However, there is a trajectory that your parent will likely follow as they move through the four stages.

Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease

Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease is a newer addition to the recognized stages. The National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association added it because evidence points to changes to the brain happening before symptoms appear. No criteria is currently available to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease in the preclinical stage. However, research is underway to study potential biomarkers that may one day indicate the presence of the disease before symptoms present.

During this stage, dementia and memory loss are not easily detectable. Your parent functions normally and exhibits their typical behaviors, personality and emotional traits. Preclinical Alzheimer’s can last for years before the disease is detectable.

Early Stage Alzheimer’s

In early stage Alzheimer’s disease, the person with dementia first senses that something is missing or their memory is “slipping.” This is often when a diagnosis is made. Declines are minimal, and it’s usually possible to safely live alone.

Your mom or dad might drive, manage their bills and household, and socialize normally. Indicators of early stage Alzheimer’s include repeated forgetfulness. Examples include forgetting phone numbers or names, having difficulty following recipes, or not understanding what common objects are used for. Typically, this stage lasts two to four years.

Mid Stage Alzheimer’s

During mid-stage Alzheimer’s, memory loss is more pronounced and increasing. This is typically the longest of the three primary stages (early, mid and late), usually lasting two to ten years.

Your parents might noticeably exhibit confusion and behavior and personality changes. This prompts questions about safety and living alone. It leads many families to consider placement in a memory care facility or professional in home care.

Late Stage Alzheimer’s

In the final stage of Alzheimer’s, the loss of independence and identity are most pronounced. Your loved one might lose the ability to respond to their environment, recognize and respond to family caregivers, and even communicate.

Intensive, around the clock care is needed. Hospice Care for late stage Alzheimer’s is one recommendation your loved one’s physician might make. Late stage Alzheimer’s typically lasts from one to three years, but sometimes only a few weeks.

Coping with Changes as Dementia Progresses

Through each stage of Alzheimer’s, your loved one will experience many changes. Understanding this and preparing for the changes ahead makes it easier to care for a parent with dementia at home.

Cognitive Changes

Cognitive changes refer to changes in higher brain functioning. They impact memory and reasoning. While some changes in cognition are common as we age, they are more severe for the person with dementia.

Common cognitive changes for seniors include:

- Slower recall speed and delayed problem solving

- Decreased reaction time and attention span

- Challenges learning new things, focusing and concentrating

The person with Alzheimer’s experiences:

- Disorientation – becoming lost in familiar places or confused about time and day

- Memory Loss – varying levels of difficulty remembering names and faces

- Decline in Ability to Socialize – a lack of interest in socializing. Later, a loss of understanding about how to socialize

- Coordination and Motor Functioning Skills – varied loss at each stage of Alzheimer’s

- Cognitive changes – often gradual at first but always increasing. Awareness of this is helpful

Journal your loved one’s progression. Regularly communicate with their physician. Talk to your loved one about their wishes and goals early and often. Look to resources like the Family Caregivers Alliance to find helpful dementia support groups and local support.

Emotional Changes

As the brain struggles to process information, emotional changes are common. The person longs for the return of independence, routines and their social life. A few of the more common behavioral challenges of Alzheimer’s include:

- Frustration and Anger – The senior feels frightened, embarrassed or confused about changes they are experiencing. The result is sometimes deep anger, resentment or frustration. Additionally, anger and frustration are common if the senior needs more help with ADLs or household chores. Even when help is offered, accepting it may be challenging.

- Depression – If your loved one is feeling isolated, watch for depression. Determining whether this is diagnosed depression or a symptom of Alzheimer’s is sometimes challenging as a family caregiver.

Depression as a diagnosis and depression related to Alzheimer’s mimic each other. Both share symptoms like apathy, sleep troubles or memory loss. However, there are differences. Depression with dementia often involves changes in mood, agitation, and anxiety. Feelings of guilt, suicidal ideations, and reduced self-esteem are not as common with Alzheimer’s disease.

- Anxiety – This results when your loved one experiences difficulty processing information or adjusting to new environments. When common memories begin to fade, it’s difficult to cope. The struggle to make new memories also increases. Insomnia, frequent pacing and clinging to common people and objects are all indicators of anxiety in person with dementia.

Strategies to support a senior with dementia’s emotional health include:

- Provide reassurance and remind your loved one that they matter

- Break down complex tasks into small, easier to process steps

- Encourage activity and socializing as appropriate

- Recognize and respect the person’s feelings

- Redirect the senior away from painful or uncomfortable conversations or memories

- Approach from the front so the senior is not startled or surprised

Difficult Behaviors

Your loved one may, over time, lose the part of their psyche that tells them to follow societal norms. This can lead to the development of dangerous and difficult behaviors.

While caring for your parent with dementia at home, you might notice an increase in cursing or lashing out verbally or physically. Your loved one could increase their use of alcohol. They might develop mistrust or exclusively trust one person.

Sundowning Syndrome is also possible. This is an increase in confusion, uncertainty about location or identity, and agitation from dusk into the early morning hours.

According to the National Caregiver Alliance, behavioral issues are one of the biggest challenges a family caregiver faces. If your loved one is experiencing them, your loved one’s geriatric physician is an excellent resource to turn to.

Changes in behavior are sometimes caused by medications or an underlying condition. A thorough exam is warranted.

Strategies for coping with difficult behaviors:

- Remain calm and remind yourself that these behaviors are not intentional

- Use calming words. Avoid shouting or mimicking angry outbursts

- Approach your loved one in a comfortable, direct way. Avoid surprising them or approaching too quickly

- Learn your parent’s routines, and try to follow them. Keeping a journal of the times of days or activities that spark certain behaviors helps

- Provide reassurance and acknowledge how your loved one is feeling

- Offer the senior two or three options so that they feel more in control

- If an environment sparks certain behaviors, move to another room or change activities. Dim lights or use scented oils to create a soothing effect.

- Sometimes, it’s best to step away and let someone else take over

Respite Care, Caregiver Health and Behavioral Changes

Caring for the caregiver is essential, especially when difficult behaviors present. Taking breaks makes it easier to cope with difficult behaviors. It also provides family caregivers with emotional strength to continue providing care. This is the reason why respite care is so valuable.

Monica Moore, MSG, Community Health Manager for the Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research at UCLA (Easton Center) explains this best.

Monica states, “The Family Caregiver Alliance has found that 50% of caregivers die before the person they are caring for. This dramatic number is due to the fact that so many caregivers ignore their own physical and emotional needs while they are entrenched in caregiving. Finding time and resources to provide respite to caregivers is essential. Hiring in home help is not always for the person with dementia, sometimes it is for the caregiver. It provides a chance for a caregiver to focus on something other than the person they are caring for, a chance to take a walk, take a bath, or just breathe.”

Physical Changes

Physical changes are also common with Alzheimer’s disease. The senior’s feet might shuffle or drag. Balance troubles and difficulty moving from sitting to standing or standing to sitting are common. Weak muscles and fatigue are symptoms, as are changes in wake / sleep cycles.

Slow decline while caring for your parent with dementia at home by encouraging your loved one to remain active for as long as possible. Even short walks with assistance or simple stretching exercises are helpful. Empower the senior with dementia to remain more independent by offering assistance only when needed.

Early Planning for Your Aging Parents

The Importance of Health Care and Early Detection

A relationship with a geriatric physician is invaluable for dementia patients. Exams provide valuable information about memory loss. An early diagnosis also offers options for treatments and medications that can slow the disease’s progression.

A dementia evaluation includes a physical exam, bloodwork and medication review. Doctors also conduct a mental health and cognitive evaluation. They gather family and previous health history.

Advanced Care Planning

Advanced care planning protects your aging loved one’s finances and health. It can ensure that their wishes and goals are respected even if they can no longer express them.

Discuss goals and wishes with your parents. Ask for their thoughts about finances, placement, aggressive health care treatments, hospice care, and a living will. Conversations are most effective when they happen early and often.

Part of this process includes granting durable power of attorney to a trusted adult. This will legally allow that person to make important decisions if and when your parents are unable to.

Living Alone with Dementia

One of the most difficult conversations to have with a senior with Alzheimer’s involves discussing living arrangements. Living alone with dementia is risky, but most seniors prefer to age in place. As the disease progresses, risks of falling, wandering, leaving a stove on, forgetting medications, or experiencing isolation and loneliness increase.

The stage of the disease and safety are important factors to consider when discussing aging in place. Now is the time to consider in home care, support that can prove invaluable to a senior coping with dementia.

“When a family comes to me with concerns about a loved one with dementia, I often recommend a home care provider so the older adult can safely remain at home for as long as possible.” states Jill W. Love, Geriatric Care Manager with Peters and Love. “Caregivers provide valuable assistance with meal preparation, personal care, medication reminders, companionship, supervision, and so much more. Since caregivers get to know their clients very well, they have the ability to improve the older adult’s quality of life through engagement and personalized care. As a geriatric care manager, I rely on the caregivers’ observations and insights when considering changes to the care plan, and I consider them an integral part of the care team.”

Remaining in a familiar environment is far less disorienting for a person with dementia than moving. People with dementia also benefit from the set routines and secure feeling of being in a place that they know. However, an unsafe home environment poses risks, so safety and support are essential.

Whenever possible, it’s best to have these conversations prior to receiving a diagnosis. Otherwise, you risk your parents not being able to weigh in. Accepting home care, moving, or going to a memory care facility are all difficult if the person isn’t involved in decision making.

Sometimes, it’s easier to take smaller steps rather than make one big change. If your aging parent expresses that they want to remain at home:

- Ask them to accept help with a select few tasks first

- Discuss part-time home care or respite care and family support

- Interview the agency you’re considering, and involve your parents

- Start slower. Increase hours as the disease progresses

- Make the goal to stay home for as long as possible even if not permanently

Preparing the Home of a Loved One with Dementia

While caring for a parent with dementia at home, don’t ignore their environment. Adapt the home in a way that helps to compensate for changes occurring in the brain. This helps to increase safety.

Bedroom

Safety in the bedroom involves making the space easy to see and easy to move around in.

Add lighted pathways and non-slip flooring for middle of the night bathroom runs. A comfortable and not too high or low bed makes for easier transfers. Limit the number of items on the nightstand or dresser to avoid confusion. A brightly colored quilt visually defines the bed.

Make the space visually appealing but not one that encourages “hanging out”. Spending too much time in the bedroom can increase risks for loneliness and isolation.

In the closet, remove all but four or five of your loved one’s favorite outfits (ask for their opinion) from the closet. Have a caregiver lay out each outfit in the order that the senior gets dressed. This makes dressing easier and helps your loved one to feel more independent.

Bathroom

A person with Alzheimer’s has challenges seeing the edges of surfaces in bathrooms, especially if they are all one color.

Add bright accents to help. Paint the trim of the door red or add a colored toilet seat so these elements stand out. Colored, non-skid tape makes it easier to recognize the floor of the shower and tub’s edge. Tape is also helpful around the sink and toilet.

Mark the hot and cold faucets with bold words and bright colors to prevent scalding. Turn down the temperature on your hot water heater for safety. Add a tub seat or bench and a handheld shower spray to make bathing alone easier. Grab bars by the tub and toilet also help prevent slips and falls.

Kitchen

The kitchen is filled with sharp objects, heated surfaces, and dangerous chemicals. Keep them out of sight to restrict access.

Knob covers are a great stove addition to prevent burns. Add these if your aging loved one has someone in the home to help them prepare meals.

Label drawers and cabinets. Use words in big block letters or even pictures to indicate what is inside of them.

Have a working smoke detector with fresh batteries and a fire extinguisher easily accessible in the kitchen.

Other Living Areas

Across the home, eliminate clutter. This creates safer walking paths and it makes rooms less visually overstimulating. Consider pairing down furniture with the goal of simplifying the environment.

Shiny floors are sometimes slippery, and your loved one might perceive them as wet and difficult to walk on. It’s best to avoid them.

Secure throw rugs to the floor to avoid trips and falls. Better yet, get rid of them. Depth perception is often an issue for people with dementia. Mark stairs with colored duct tape or carpet tape to ensure they’re easier to see.

Preventing Wandering

Living at home increases the risk of a person with dementia wandering, getting lost, and injuring themselves. Certain safeguards can help.

Register your loved one for the Alzheimer’s Safe Return Program. Be aware of all the exit doors from the home, and install slide bolt locks on them. If your loved one is tall, install locks lower on the door. If they are short, install them higher.

Adding motion sensors to the door provides a warning if your loved one is trying to leave. Disguising the door is another strategy to try. Paint the door the same color as the wall or hang a curtain to give the appearance of a window.

A fenced outdoor courtyard and appropriate supervision create a safe space for wandering. Regular companionship and memory stimulating activities also reduce wandering. Consider hiring a caregiver to help with this while caring for your parent with dementia at home.

Keeping your aging loved one home requires effort, but the payoffs are substantial. To realize these benefits, it’s important to understand the disease and your options.

Salus Homecare is here to help you in caring for a parent with dementia at home. Our professional team can answer your questions and get you the information you need. Contact us anytime to schedule a free, no obligation consultation with a knowledgeable case manager.